On the 17th of October 2019, approximately one hundred Lebanese protesters took to the streets of Beirut to express their anger over a WhatsApp tax, newly imposed by their government. It was the beginning of the Lebanese Revolution, a wave of daily protests ranging from tens of thousands to even millions of Lebanese rising up against a deeply corrupt government. Talking to a young Lebanese female, I quickly learned that the WhatsApp tax was nothing more but the proverbial last drop. “This revolution has been in the making over the last thirty years”, she said.

This revolution has been in the making over the last thirty years

People have been protesting on a daily basis for the last month to fight a government that failed to lead Lebanon after its extremely violent Civil War (1975-1990) into a state that provides its citizens sufficiently with basic needs such as water, electricity, jobs, education, medical health care, public spaces, LGBTQ and women’s’ rights. There is a deep economic crisis enfolding and the unemployment rate is almost forty per cent. The prime-minister Hariri has resigned, and people demand a new, non-sectarian and non-corrupt government. After a month of peaceful protests, clashes have lately occurred between the protestors and the heavily armed Hezbollah – Iran-backed Shiite Muslim militia – possibly taking the revolution in a more violent direction.

What struck me as a coincidental witness is is two things: first is that our Western identification with what’s going on in Lebanon is somehow blurred by the geopolitical positioning of the country as a Middle-East state

I ended up as an accidental by-passer of this impactful revolution while visiting friends in Beirut. Walking the streets of the city at night made me feel how this revolution has an uncontrollable thriving energy. Although Lebanon is heavily divided into several different religious, social and political groups, the revolution is supported by young leftist students but also by well-off Lebanese, by Christians and Muslims alike. In Beirut’s expensive night clubs the crowds are shouting ‘thawra!’ (‘revolution’ in Arabic) in between the Western-style DJ sounds. Plans for revolutionary activity are being made on the streets of an uptown Beirut area. On the central Martyr Square, next to the blue Muhammed Al Amin Mosque, rises a huge clenched fist, a major symbol of the revolution. Apart from setting up roadblocks, people are singing, dancing, shouting, and making a lot of noise in front of the parliament by banging pots, sticks and drums against a metal construction wall. ‘The Egg’, a former cinema that was closed down by a real estate company after the Civil War, has been reclaimed by the protestors who use it as a revolutionary platform.

What struck me as a coincidental witness – who happens to write a PhD thesis on the Indonesian revolution on the island of Bali – is is two things: first is that our Western identification with what’s going on in Lebanon is somehow blurred by the geopolitical positioning of the country as a Middle-East state: having Israel on the southern border, Iran-backed Hezbollah territory and protests that are also turning against the influence of the United States. But geopolitical considerations seem far away from the protestors in Lebanon, who desire nothing else than most people wish for: non-sectarian governments that invest in the country and people’s rights to basic living standards, creation of jobs and a sense of safety in their identities. The revolution has many similarities with other protest movements or revolutions that have taken place or that are taking place right now, like in the Republic of Chile, Hong-Kong, Iraq, Iran and Prague.

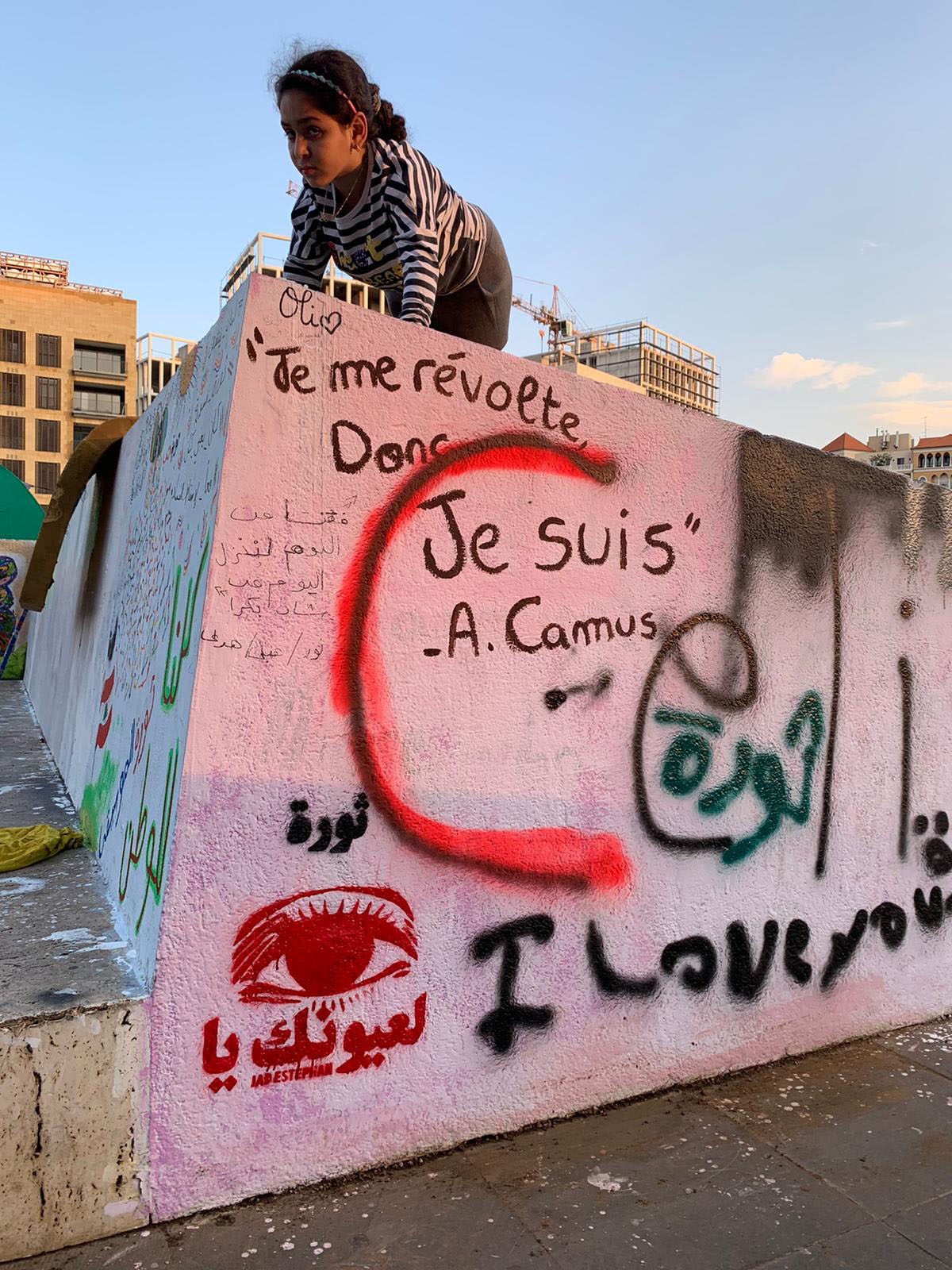

Second: that despite the possible violent or otherwise negative outcome of the revolution, Lebanese protests are optimistic and full of hope. This is also reflected in the attempts to create this better world within the public spaces they reclaim, as well as in the revolutionary language they apply by using graffiti, street art and other creative forms of expression. These powerful tools to express a political opinion are in some media referred to as “cheerful” but they actually reflect the political heart of the revolution. The messages also show how the revolution in Lebanon is inspired by universal ideas and by other revolutions.

These powerful tools to express a political opinion are in some media referred to as “cheerful” but they actually reflect the political heart of the revolution.

On the 30th day of the revolt we walk the streets of Beirut, accompanied by Aya, a female Lebanese student. She’s a guide for the Alternative Tour Beirut, a four-hour walking tour from the east to the western side of the city, with an emphasis on the political and cultural history. Graffiti statements and street art cover the city centre: ‘we are done,’ ‘eat the rich,’ ‘fuck the system’ and ‘I rise to be vigilant.’ Among the highlights of the tour are the omnipresent traces of the fifteen year’s Civil War that Aya easily connects to today’s revolution. One of the epicentres of the revolution in Beirut is the Ring Road, a highway that connects East to West, near the old demarcation line during the Civil War, the so-called ‘green line’ where roadblocks were now in place.

In the west of the city, a huge painting of a gender-neutral child playing with the inside of a computer covers an entire building as a tribute to the thousands of children who died during the Civil War. A few blocks down, the war-torn building of the strategically located former Holiday Inn Hotel, which was used during the civil war by both striding parties to kill their enemies (often throwing them from the balconies to save bullets), remains standing as a gruesome lieu de mémoire. The war divided Lebanese into Christians and Muslims, rightists and leftists, and an estimated 150.000 up to 200.000 people were killed. It was a war that had its roots in the 1943 independence from the French, who were benefitting the Christian population in terms of power and jobs by means of ‘divide and rule’. But as Aya explains, it was also caused by the destabilizing factor of the PLO, Yasser Arafat, who took refuge in Lebanon in 1970, and who divided the Lebanese between those who supported the Palestinian cause versus those protecting the economy of the Paris of the East at all cost.

The war was afterwards silenced in the Lebanese history schoolbooks, mainly because people couldn’t come to a definite agreement on its course. Reconciliation never occurred. “Our history books stop in 1943”, Aya says. She thinks her father was involved in the war, like most of his generation, but he never speaks about it. “Younger generations are now asking questions.” The revolution is in that way also breaking a long-time silence that had evolved after the war. When Aya is asked if the outcome of the revolution could contribute to reconciliation amongst the different religious and political groups, she pauses a moment. Then she replies “it all depends on the outcome of the revolution.”

Younger generations are now asking questions. The revolution is in that way also breaking a long-time silence that had evolved after the war.

The Civil War is also one of the reasons that older Lebanese, many of whom still bear the wounds of the war, are worried about the revolution. “Lebanon is Lebanon,” one of the older taxi drivers says. “Just let me do my job.” Nothing is ever going to change, he appears to imply. He is potentially also referring to the long-time involvement of foreigners in their country: from Phoenicians to the Crusaders to the Ottoman Empire and the French. The country is now heavily influenced by the rising tensions between the United States and Iran. The former tries to diminish the influence of Hezbollah – who has more power in Lebanon in terms of military capacity than the official army – through economic sanctions that are crippling the whole country. An upper-class Lebanese man asked me about the upcoming celebration of Independence Day from French occupation in 1943: “what are we celebrating independence for? We are still dependent.” People seem to be used to it, however. “What can we do?” a taxi driver said. “America is a very powerful country, we are in fact dependant on them.”

We walk into ‘The Egg,’ the former cinema that was closed down by a real estate company after the Civil War. Aya explains how important public spaces are to the Lebanese youth and how painful it is they are almost all privatised by politicians. WhatsApp was one of the last private spaces remaining where people could share ideas. When she and her friends want to come together and create new intellectual ideas, they either have to stay at home or meet in one of the many bars in Beirut: nice, but crowded and very expensive. To cross over sectarian lines, public spaces are of pivotal importance. The graffiti statements on the many concrete walls inside ‘The Egg’ scream for change. There are expressions against corruption, racism, homophobia, war, and the police: ‘Blind leading the blind,’ ‘Make Lebanon queer again,’ ‘Corrupt pigs,’ ‘No more,’ and ‘If not now when?’

Claims for social justice and women’s rights are very visible in Beirut. “Riot girls,” says one of the graffiti writings, “bitch talks”, or the image of a heroin Marianne-like woman, symbol of the French revolution. An upper-class Lebanese-French woman told me how important this revolution is for Lebanese women. “We are now finally finding our voice as women, this revolution is an important moment for us.” One of the women activities was to form a cordon humanitaire, walking between the protestors and the army, to protect the protestors from the military. They held candles and hit pots and pans with spoons. Aya was one of those women. “For me, this was the most special and precious moment of the revolution. We as Lebanese women are rising up, we are fighting for a better future, for democracy, for better education, for social justice.” Women were preventing fights amongst men during the protests by putting themselves to the frontlines. Aya’s spirited speech over her deeply felt conviction to join the revolution made one of the female Western tourists silently wink away a tear.

We are now finally finding our voice as women, this revolution is an important moment for us. One of the women activities was to form a cordon humanitaire, walking between the protestors and the army, to protect the protestors from the military. They held candles and hit pots and pans with spoons

What is striking in the political graffiti is the representation of other revolutions. Visible are quotes of Lenin resembling the Russian Revolution of 1917, ‘Guillotine’ referring to the French Revolution, an image of the Cuban revolutionary Che Guevara, Spanish lyrics of the protests in Catalonia: ‘The streets will always be ours’, ‘power to the people:’ the civil rights movement in the United States and the famous words of French philosopher Albert Camus, ‘Je me revolte, donc je suis’ with a meaningful ‘I love you’ underneath. There is also an image of John Lennon, who was also an activist against the Vietnam war, on one of the walls in the Egg. In 1980 a ‘Lennon wall’ was created in Prague, a short stretch of wall opposite the French embassy on which a huge portrait of John Lennon was painted, who had just been shot in New York. It attracted young people who were arrested and beaten by the police, but who started to paint political messages over and over again. On the 17th of November this year, on the 30th Memorial Day of the ‘Velvet Revolution’ of 1989, the year of the fall of the Berlin Wall, one million Czech people took to the streets of Prague to protest against a corrupt government. As in Lebanon after the Civil War, it appears that the longed-for peace in the Czech Republic failed to bring true democracy.

The revolution in Lebanon reminds us just how much people all over the world, in fact, want the same things, and are inspired by others and universal ideas of a better world.

The revolution in Lebanon reminds us just how much people all over the world, in fact, want the same things, and are inspired by others and universal ideas of a better world. “I am not an idealist,” Aya responded when one of the tourists asked her about the prospects of the revolution. “You can meet us half-way.” The revolution is in favour of change, she says. It may seem idealistic in its goals, but people have serious demands, Aya implies. Although the faith of the revolution – that is now taking a more grim direction – will probably be influenced by global powers, this uprising is more than a pawn in a geopolitical game. In its fearless, uncompromising conviction in the justness of its cause lies its power, as well as in its lack of alternatives. Its message of hope and humanity extends far beyond the national borders of Lebanon, or even that of the Middle-East.

Recommended watching: De Slag om Libanon is a series of reports for Dutch TV by reporter Danny Ghosen about the situation in Lebanon, recorded between June and November 2019 (language: Dutch)