This article is an outcome of the workshop series ‘’Bon Buzz‘’. Bon Buzz challenges young Chadian journalists to bring nuance to polarising issues in society through personal stories.

It was on a blazing Wednesday afternoon, 11 September 2024, that I went to the Chagoua district in the 7th Arrondissement to meet Claudia at the Transformers’ headquarters, a place symbolically called the “Balcony of Hope”. The 1-storey building, painted in creamy blue and yellow, is easily distinguishable with its sign displaying the party’s name.

At the entrance to the HQ, I pass a motley crew of young men and women exchanging greetings. As a good Chadian, I shake a few hands before entering. This is where I meet Claudia: dressed in a blue dress with stylish glasses and dreadlocks reminiscent of a media star. She is vice-president of the party and embodies the hope of change.

The protocol staff greet me warmly and direct me to the lounge where I await her arrival. While I waited, I was struck by the inspiring atmosphere of the place: the walls were adorned with writings advocating justice and equality. Graffiti depicting Nelson Mandela and Martin Luther King add a historical dimension to this space dedicated to social struggles.

The varied scents of visitors waft through the air as I try to learn more about this daring woman who defies established norms. Who is Claudia really? What are her motivations? And how does she navigate this political world where every step is scrutinised?

Our encounter with Claudia will not only be that of a committed woman; it will also reflect the challenges faced by all those who aspire to play an active part in government in Chad. Through her life story, we will explore not only her personal struggles but also those of an entire generation of women determined to change their destiny despite persistent socio-cultural obstacles.

Claudia Hoinathy is a determined and resilient woman from Sarh, Chad. Born into a family that values education regardless of gender, she quickly developed a passion for the sciences. After obtaining her scientific baccalaureate, she moved to N’Djaména to study biology. Although her path was strewn with obstacles, including academic delays and health problems, Claudia never gave up her desire to learn.

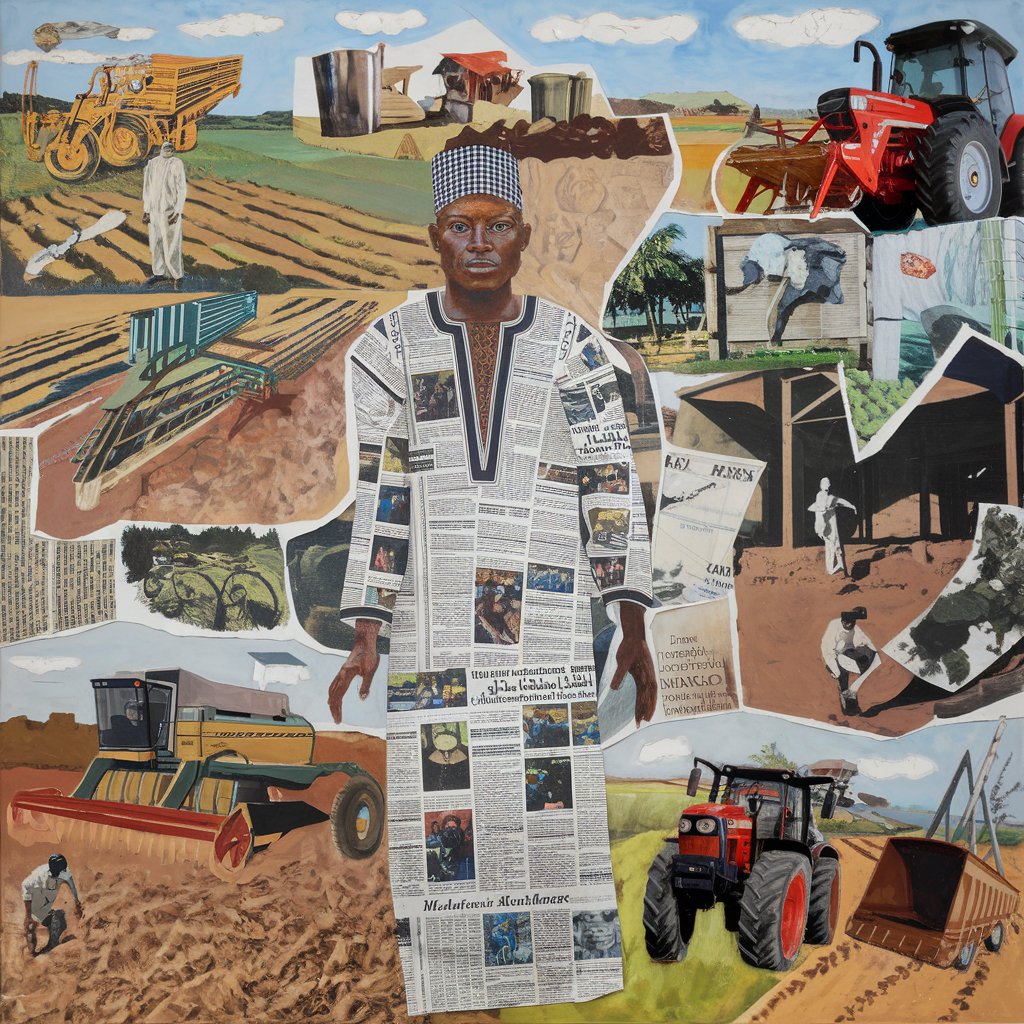

She eventually obtained a Brevet de Technicien Supérieur (BTS) in agro-sylvo-pastoral with a specialisation in the environment. After working for eleven years in the banking sector, she decided to go back to school to study for a Masters 2 in the environment.

On the political front, Claudia joined a party by chance, attracted by the development vision of the ‘Les Transformateurs’ movement. Although she initially had reservations about politics and its players, she was convinced by the party chairman and became vice-president. She emphasises the importance of hard work in gaining respect in an often male-dominated environment.

Claudia faces challenges as a woman in Chadian politics, but she remains determined to prove her worth through her skills and commitment. She firmly believes that respect is earned through hard work, and that women must redouble their efforts to gain recognition in this field. Her philosophy is based on the idea that speed and perfection in work are essential to stand out and succeed.

Her vice-president and president colleagues have no regrets about having her by their side, and respect her as they should. However, other people feel complexed by the woman she is, a real political force. She tells us that in the course of her career, she meets men who think she’s running out of steam and suggest she should stop. These are questions or suggestions that they have never dared put to her male colleagues. They think that women are weak and burn out quickly, unlike men, who have stamina and perseverance.

She also highlights the case of some women who feel she dares too much. For them, it would be preferable to support a man rather than a woman, even if the latter is just as capable. They say this because of their own inability to learn and understand that not all women are the same. Some can even surpass certain men in their skills.

She concludes by saying that she is often more opposed by women who spend their time questioning her intellectual level, which has propelled her career, without seeking to improve themselves. She points out that these questions have never been asked of her male colleagues.

Claudia tells us with conviction that the accusations that some women use their sex to gain access to positions are not only unfounded, but also reflect a much more complex reality. Women must stand out for their work, their intelligence and their know-how, rather than for their beauty.

She talks about gender equality and the 30% of jobs reserved for women by the government, a measure welcomed by some. As a former observer from outside government, she condemned this decision: giving 30% representation to a female population that accounts for 52% would be an insult to women. She shares the same concerns as those calling for parity.

At this stage, when she has embarked on a career in politics, she realises that the problem also lies with some women themselves: you can’t demand equality while looking for the easy way out, or accept excuses simply because you’re a woman. She expressed her surprise at the women in the assembly thanking the head of government for the seats given to women; thanking someone for a legitimate right shows an inappropriate form of humility.

Furthermore, she notes that women have difficulty in filling the 30% quota, as shown by past elections: out of a total of 52% of the population, only 10% were female candidates. In her view, it is legitimate for decisions to be taken without taking women into account if they do not actively participate in the political process; they marginalise themselves by accepting the place that society assigns to them.

On the other hand, VP Claudia points out that some women enter politics as followers, without conviction or a clear understanding of the political visions of their leaders; they then become pawns used to harm or for other unspeakable ends. Many people still think that women have nothing to contribute intellectually; yet there are brilliant women whose potential remains stifled or bought at the price of silence or inaction.