Camp for displaced people in Sénou, Bamako. @ Sjoerd Sijsma, 2021

Since 2016 violent conflict in Central Mali has taken the lives of at least 6,000 people and has led to the displacement of at least 350,000 IDPs towards the South (Sikasso and Koutiala) and towards relatively quiet places in Mali, such as Sévaré, Sokoura, Sofara. The violent scene is defined by an amalgam of militia, with religious vocation, the jihadi, or based on traditional organization, like the Donzo. These militia also organise around ethnicity as is the case with Dana Ambassougou that are mainly Dogon, or the Fulani militia. Other parties are the national Malian army (FAMA) and international intervention forces (Barkhane, G5, MINUSMA). The military interventions have so far not resulted in less violence, instead the past year was more violent than any year before. Large parts of Central Mali are left in a governance vacuum, as the State is practically absent and local leaders often also had to leave.

A possible response to the violence is the creation of local peace pacts. On social media these pacts are announced, defended and discussed. International and national media discuss these pacts often in a hopeful manner. I will try to understand the balance between peace and violence that these pacts create in the area and how this relates to the consolidation of power of the Jihadi and other militia as seems to be the tendency in Central Mali.

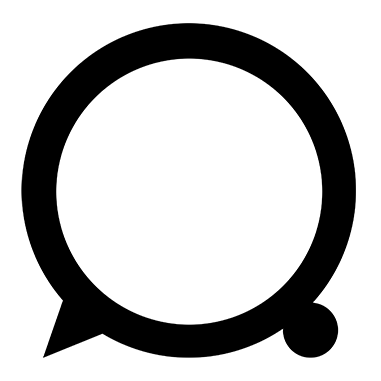

Figure 1: Civilian fatalities Mali; ACLED reporting

Figures on the casualties of this war are diverse; I also share statistics with a Malian in the diaspora who follows the conflict via his informants in Mali and double checks all figures. His estimation for death since 2015 is that over 6000 people have died, and as he adds these are modest estimations as many cases could not be double checked; he fears that the real figures are higher.

Alerts: Jihadi expansion

An alert message from the reporter ‘enfant de Bankass’ circulated in Whatsapp groups on the 6th of January 2021, in which he states that the communities of Bankass search for protection with the Jihadi groups, who have ‘invaded’ the area. He says that with the arrival of the military regime (after the coup d’état 18 August 2020) the population had hope, but this hope has gone and there is no other solution than to surrender to ‘the enemy’. Also his analysis points us to the fact that the entrance to Mopti, a capital city in Central Mali, may become accessible for the Jihadi groups. This has however, not materialised after he wrote this post.

Already in 2017 two districts in the Inner delta (Dialloube, Tenenkou) were occupied by the Jihadi groups (see blog post Moodi), and 2017 till now have shown an increasing influence of these Jihadi groups in the Hayre (Douentza-Hombori region) and the region of Mondoro (towards the border with Burkina Faso). In fact, Jihadi rule almost all Central Mali (Mopti Region and parts of Segou Region), with exception of the larger cities. Recently violent attacks in more southern regions, such as Sikasso and Koutiala, seem to announce a next phase in the increase in Jihadi power in Mali.

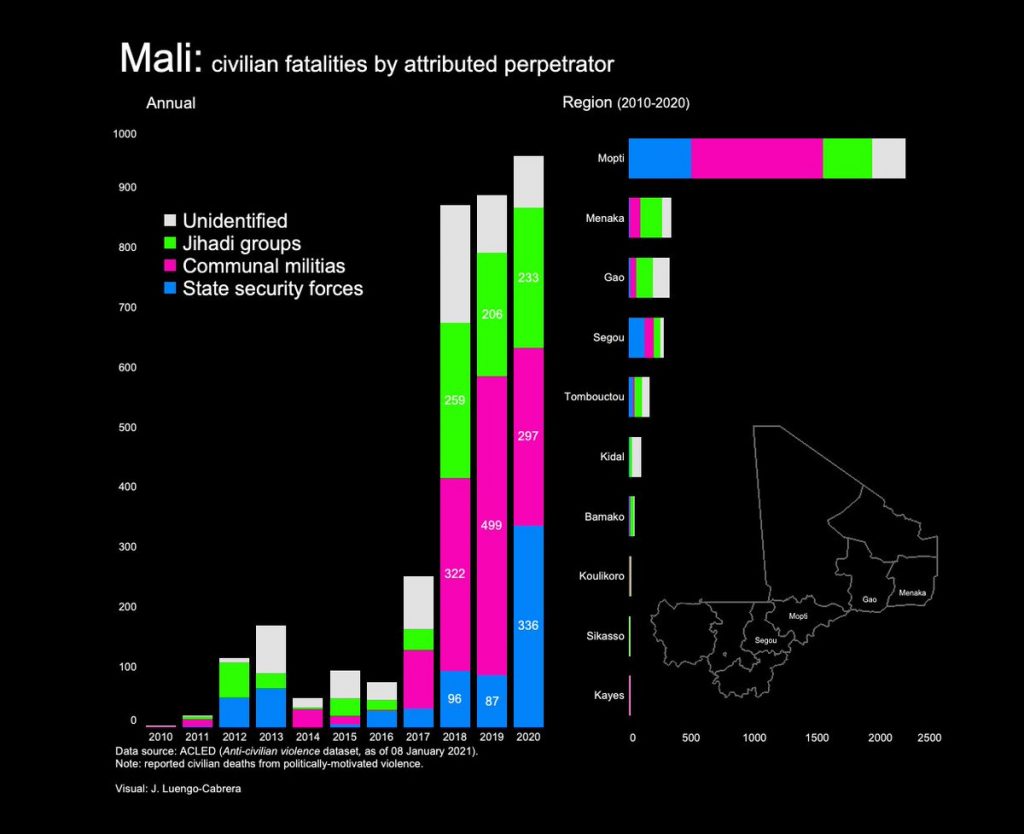

Figure 2: Attacks in the South

Figure 3: Reaction to the post in fig 2, in the WhatsApp group of V4T

These discussions on the V4TA WhatsApp group and other message that circulate on social media confirm the southward movement of Jihadi attacks, and responses of Donzo; indicating that the tensions and the politicization of ethnicity is on the rise and moving from the Centre to the South of the country.

Who are these men in the bush?

A first question we need to answer is who are these Jihadi that apparently become increasingly powerful? In another text I explained how from dispersed organized militia gradually Katiba Maasina emerged with Hammadoun Koufa as its leader. Hammadoun Koufa who is part of the collaboration between various Muslim groups that operates in the Sahel and Sahara, JNIM (Jama’a Nusrat ul-Islam wa al-Muslimin’, support group for Islam and Muslims), who assigned Central Mali to him. Other armed groups pledged allegiance to Hammadoun Koufa and today Katiba means the organization of groups of young men in the bush, from where they control vast areas, and attack military targets, and kill people who they define as traitors. If possible, they will hold a trial for these people in their own Sharia Court, and then decide if they be executed or can go free. They promise the population protection if they adhere to their rules, hence pay zakat and follow the Sharia. Then relative calm can return to the regions. The majority of the Jihadi fighters are Fulani, who joined these groups out of frustration with past injustice to their community, the insecurity situation from both FAMA and Donzo actions and the absence of the state in their home areas after the conflict broke out in 2012 (see a text from 2015). One of the returning arguments of the Jihadi groups, also phrased in the preaches of Hammadoun Koufa is that they fight against the State and the invaders (the French). They say not to touch the population except by bringing them the right faith. Their violence is directed at the FAMA and international intervention forces and all those who collaborate with them.

Herder-Farmer opposition?

In the presentation of the conflict today the main military adversaries of these Jihadi groups are the Donzo militia who also partly joined forces with the FAMA. So far, they have not been able to drive back the Jihadi groups: instead their actions have been very violent and directed against civilians, of specific ethnic origin (mainly Fulani). The FAMA have also been accused of being biased/racist in this conflict in that they target civilian Fulani more than other ethnic groups. This has resulted in the explanation of the conflict in ethnic terms, often presented as a farmer-herders conflict. However, if we consider the development of these livelihoods over the past decades in which they have both become mixed livelihoods economies, the farmer-herder opposition is too simplistic to understand the violence we are facing today. Other factors are also important; such as the changing ownership of cattle into the hands of rich urbanites and politicians, the expansion of farmland into the originally pastoral areas (and vice versa), and the lack of ‘good’ governance in the fragile political situation of Mali. The farmer-herder opposition is hijacked in a fight over resources of various kinds, and of access to land by two rival groups; the Donzo vis-à-vis the Jihadi groups. Accusations of being Jihadist also target ordinary citizens. Attacks lead to retaliatory attacks and this has been the basis of the increasing violence.

Fragile peace agreements

Peace in Central Mali seems to be farther away than ever. Local agreements have been embraced as one of the ways to get out of the violent conflict in Mali. This search for peace has been monopolized by Non-governmental organizations and (inter)national associations. Such as Henry Dunant Centre (Humanitarian Dialogue) (HD), who have been working in Mali since 2011 and already worked on peace agreements before the conflict erupted in 2012 in the north of Mali. HD works with the hypothesis that the basis of the conflict is the antagonism between farmers and herders. In January of 2021 they have concluded a 4 months process to reach peace-pacts in the cercle of Koro by signing three agreements on resp. 12, 22 and 24 January. A fourth agreement was concluded on February 7, in the district of Bankass. The negotiations were between representatives of Fulani (herders) and Dogon (farmers) communities, armed groups and some leaders. These agreements were in fact a re-do of agreements concluded in 2018 but that in the meantime did no longer hold. Also, the associations Tabital Pulaaku, Gina Dogon, the Carter foundation based in USA, and Promediation based in Paris have been working on similar agreements in the Seeno.

Such negotiations result in pockets of (temporary) stability, occasioning the return of economic activities, such that markets are able to resume functioning or that farmers can work their fields. However, the fundamental question is whether these peace pacts that are signed between the leaders of the ethnic communities, in presence of a local representative of the government, really stop the war between Donzo, Jihadi and other militia and the FAMA? In other words, I fear that these pacts are too limited to be effective and they do not address the core of the problems.

This month, March 15, another pact was signed with the mediation of the NGO Eveil. After long negotiations the region of Niono in Mali returned to a situation of no peace-no war after a period of violence. An agreement was signed between the two warring parties in the region and this time they included the armed groups explicitly: the Donzo and Jihadi groups. The representative of Eveil explains the peace agreement in a social media post of 15 March, as a pact between the Jihadi groups, who in the post are labelled the Mujahedeen, and the Donzo. Both groups – in their own violent way – kept the population in hostage and made normal economic life impossible. The agreement was negotiated by NGOs and local leaders. Representatives of the Malian State were not actively involved. The Donzo asked the Jihadi groups to accept that women were not obliged to be veiled in public, that the Donzo can wear their outfit as they wish, and that there will be free movement for the population to work the land. On their turn the list of demands of the so-called Mudjahedeen was long: One of the demands was that the FAMA, the Malian army would leave the contested area Farabougou, a village that was kept hostage for a long time by them; they also asked that the Donzo stop their violent and exploitative acts (hence accusing them of those); they insist to practice the Zakat and Sharia; they also state that every act that reveals a sign of betrayal of their cause will be punished. There was no agreement to disarm the militias, nor was there an agreement on the possibility of the Fulani who fled the region to return to their villages.

‘C’est un début de solution. Comme on le dit mieux vaut une paix précaire que l’absence de paix’ was the conclusion of the representative of Eveil, Boubacar Ba. He also gave an interview to RFI in which he stated that the State has to accept that Jihadists are strong in some parts of the country. Boubacar Ba seeks a possible solution in the recognition of juridic pluralism in Mali, as he stated during L’Autre forum de Bamako (février 2021, voir annexe 11).

Fragile peace, for how long?

Are the recent pacts and agreements ‘for peace’ the start of a solution and for whom are they a solution? On March 22 a message, from the forum ‘Le Pays Dogon’, was forwarded on social media questioning these ‘peace pacts’ (see figure 4). They warn for the influence that the ‘peace pacts’ have on the rest of the region where the Jihadi groups also gain influence. They also state that if these ‘peace pacts’ will have no result in terms of freedom of movement and reduction of the violence, the population may in the end be forced to join/support militias again; hence increasing violence instead of diminishing it. These are the opinions of people who post in Dogon sites and groups. It might not be the opinion of the Fulani groups. In the groups that I follow closely Pinal Pulaaku, or Tabital pulaaku I did not yet come across an analysis of these ‘peace pacts’.

Figure 4: Evaluating the peace pacts

Positive is that the ‘peace pacts’ bring relative calm to the region and indeed as a colleague who works on the peace pacts in Mali told me, people return to the markets and can travel from one place to the other. However, the question is if everybody feels represented in these pacts. The root causes of the problems are not tackled. The pact must move to cease-fire between FAMA, the Jihadi and Donzo in order to have real calm, security and serenity. This would allow for the urgently needed huge investment in the regions to turn the peace pacts into something sustainable, to build a trust relationship with the state, and make the population feel that they are citizens with rights.

However, these ‘peace pacts’ also mean that in practice the state and the regular army (are forced to) give partial control over the region to Jihadi militia. The state seems to rely on the Donzo as a counter force. They seem to be incapable of providing security and cede control to non-governmental forces. It is also remarkable that they do not seem to care that NGOs are playing ‘diplomacy’ in a non-governed space.

Another important point to raise here, and that was discussed by Moodi on the site htpps://www.nomadesahel.org, is whether the domination of the Jihadi groups will in the end lead the population to give in and follow the Sharia. If the state does not show its presence and there is no return of state governance to the areas, the population will have no other choice than to radicalize. Such radicalization is difficult to undo.

This latter scenario will lead a large part of Mali into a de facto Islamic state- regime, that might have the ‘approval’ of a lot of people who have lost faith in the Malian state and do not expect any good or justice from that state. For them the ‘peace pacts’ may become a ‘peaceful colonization’ by the Jihadi groups. Whether this is a solution for a better future, I really doubt.

The proposal of Boubacar Ba (see above) could be considered as a way forward in the peace negotiations. He proposes to accept pluralism in law and incorporate the Islamic regime as a form of co-management of society. The negotiations about peace, according to Ba, should be as inclusive as possible. This would mean co-managing social, civil and community issues by involving the councils of the ruling families, the family units and ‘the people of the bush’ , e.g. the jihadi, through the cadis and paralegals. Indeed Muslim rules have been one of the juridical systems in central Mali at least since the 19th century under the Diina. However, also the Diina, was subject to revolts from within the population. I read the proposal of Ba as a call to dive deep into the history of the region, and to listen to the population. But such ‘listening’ should be inclusive as well.

This article was first published by Counter Voices in Africa, ASC researcher Mirjam de Bruijn. Republished with permission.