Photos by Gosse van Dijk

I went to Cameroon in the summer of 2016. I had been to Cameroon before as a young child, and I felt the need to return. I was inspired by the work of Pangmashi, who worked as a human rights lawyer in Cameroon, and I was interested to see how that would play out on the ground in the prisons of Cameroon. Besides that, Pangmashi was also the founder of an orphanage in his village of birth, Baba, a village close to the city of Bamenda in the North-West region of Cameroon.

The foundation of my family was involved in the monetary support of this orphanage and I was eager to get involved in this project. I contacted Pangmashi on how I would be able to contribute to the orphanage and he told me that I could go there and teach the children anything I liked to learn them. This was a bit vague for me and in the end, we decided that I could go and teach the children the basic skills of working on a computer. We figured that whatever path they would follow, some knowledge of computers might come in handy.

My younger sister, Mette, made plans to meet me in Cameroon. And since she was really into drawing and painting, we also planned to give art classes together.

The day came I went to the village for the first time. I was accompanied by Godwill, a cousin of Pangmashi. He was about my age and we got on very well from the beginning. Upon my arrival I was shown the house of the orphanage where I was going to stay and I was given a guided tour of the village and its surroundings by some of the children of the orphanage.

The village itself is situated in the fertile grasslands of Cameroon. The environment is beautiful. Like almost everywhere in the North-West region, you find yourself surrounded by clouded green hills as far as you can see.

Baba itself is not such a big village, you find the dwellings of the local “king” (in Cameroon this is called the Fon) on the highest point of the village, but for the rest most of the activity is set around the main road, which has recently been renovated and is now a free way for over speeding. However, it’s one of the best roads you find in that region.

The reason of this visit was to introduce me to the children and for me to get to know where I was about to stay, so I returned the same day to Bamenda, the capitol of the North-West province. The next time I went to the village, I brought my sister with me, and we were packed with drawing paper, pencils, notebooks, and the Dutch cookies called Stroopwafels.

We started the following day with writing classes and from then on, we would prepare in the morning and teach in the afternoons.

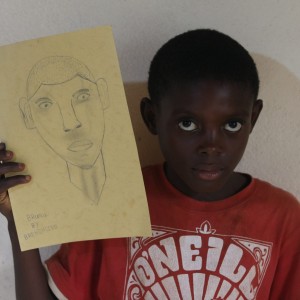

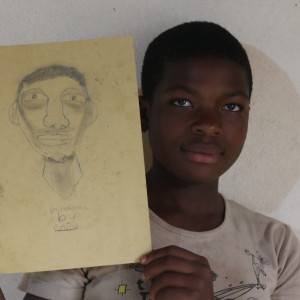

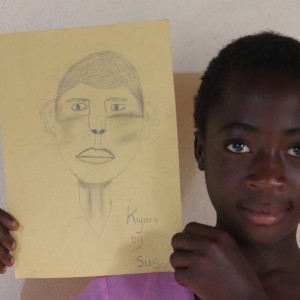

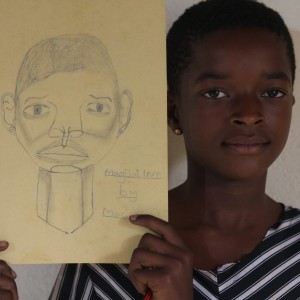

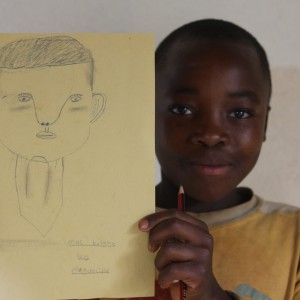

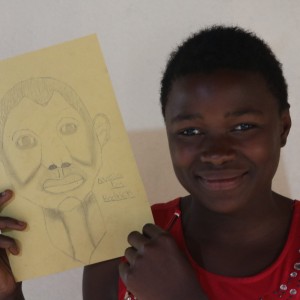

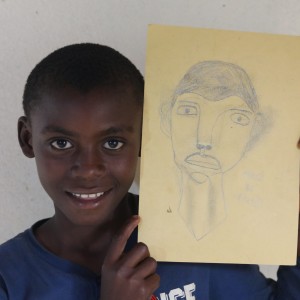

We did these art workshops for a week, assisted by Godwill. We did classes on story writing, on drawing and origami. The session that felt most successful was the day we let the children draw portraits of each other. We first let them draw a face in the empty shape of a face. And knowing there would be many mistakes, we knew we would have a lot to laugh about. Then we used the inevitable mistakes to show them how counterintuitively the proportions of a face really are.

And then the real work begun, the children would sit opposite each other and they would each draw the person sitting opposite him or her. Each time they were about to draw something new, we told them to first take some time to really look at the other person and look at the particularities of what they wanted to draw before actually drawing it.

The results of this workshop were really stunning. They made beautiful portraits of each other. You can see the results down below.

After a week of art classes, my sister had to go back to the Netherlands, so I accompanied her to the airport in Douala. After that, I returned to Baba, to start teaching the kids some things about the computer. But it felt like I came back to a different Baba. The idyll of teaching art classes was gone. Godwill had gotten into an accident on his motorcycle. And luckily, he was not badly injured, but he needed recovery time. This left me to organise the classes on my own and my days were spent with teaching the kids on how to use the computer and trying to keep order at the same time. This was a tough job, since I could only let two kids at the same time work on the computer.

I did, however, book some progress, and I’m sure some kids really got a hang of what a computer is and how to use it. What struck me most was that some of the kids were fascinated by it. Technology can have that effect on people. I let them do a typing course, let them browse in an offline encyclopaedia I had installed, let them find out things about Cameroon on their own, and I tried to get them to know how to make a document in Word. In the end the one thing they were most interested in were the games, which I figured was fine. No better way to learn than through play.

But like I wrote above, Baba felt different. The atmosphere was more tense than before. I started to pick up signs about underlying tensions in the village, I got to understand the divisions in the village and got to know about the magical events connected to strange accidents. I learned about the dark side of the village-life and it felt like it was closing in on me. However, the children were still very attentive and I was strong on trying to bring the lessons to a good closure.

One evening, walking back from some kind of errand we had to make, I told the kids that they could ask me anything and that I would see if I knew how to answer. Macbright, fifteen years old, wise way beyond his age, asked me after a short pause, what the word “revolution” meant. I was surprised, but mostly I felt excited that he had gotten the courage to ask a question, so I never asked myself why he would want to know the meaning of that word and where he could have picked it up.

I told him it could be seen as a sudden rupture in history, the beginning of something new, an urge for change. I was seeking for the right words, but of course could not find them. I wasn’t sure I made it any clearer at all.

It is only now that I see how fore boring that question was, seeing all the events that happened shortly after I left, and it is now that I understand that maybe Macbright picked up the revolutionary energy in the air, or that he had heard people talking about it, since some sort of revolution was about to happen in Cameroon.

My last days in Baba felt like the air just before a thunderstorm; heavy, humid and warm, leaving little space to breath. On the very last day, I walked to the village shop next to the main road to buy some small things. On my way there I was held up by the village “crazy”. He shouted at me that I had to leave Baba, that I was no good and that if I didn’t leave that day, they would get me. It was laughed away by the shop owner who was one of my contact persons in the village, but still it made me feel uneasy. I knew it was time for me to leave.

I had bought drawing utensils for all the kids that I had been teaching, and gave it to them on the day I left Baba, thinking of it as a nice gesture and a way to encourage them. Although I still think this was a good idea, I clearly didn’t read the situation well, because it left me being harassed by others, demanding of me that I should give them gifts too. I left the village surrounded by a small crowd, demanding a gift. It left me no space to say a proper goodbye to the children of the orphanage.

I wish it would have been a more beautiful, idyllic departure, but the truth is, that just wasn’t the case. In hindsight, I can see Cameroon was already boiling with all the tensions that were about to spill over into the conflict that is holding the country in a tight grip up until today.

I wrote that when Macbright asked me what the word revolution means, I forgot to ask myself why he would want to know the meaning of specifically that word, but in answering his question, I also forgot to tell him and the others walking with me, how bloody a revolution can be, and that it is never immediately the beginning of something new. Maybe a revolution is more the breaking down of what has been than that it is really the start of something new. It is maybe only after the breaking down that something new might emerge, if it emerges at all.

And although I don’t know if we can see the conflict in Cameroon as part of a revolution, I really hope that one day something new will emerge, though I fear that Cameroon is still very much in the phase of breaking down of what was. Maybe after that, some of these young kids can be the start of that new thing that comes in its place.

Group photo. Magdaline, standing in this photo second from right, second row, has passed away on 25 March 2021. Reasons for her passing were not discovered by the doctors. We wish her family, relatives and friends lots of strength and love.

Magdaline.