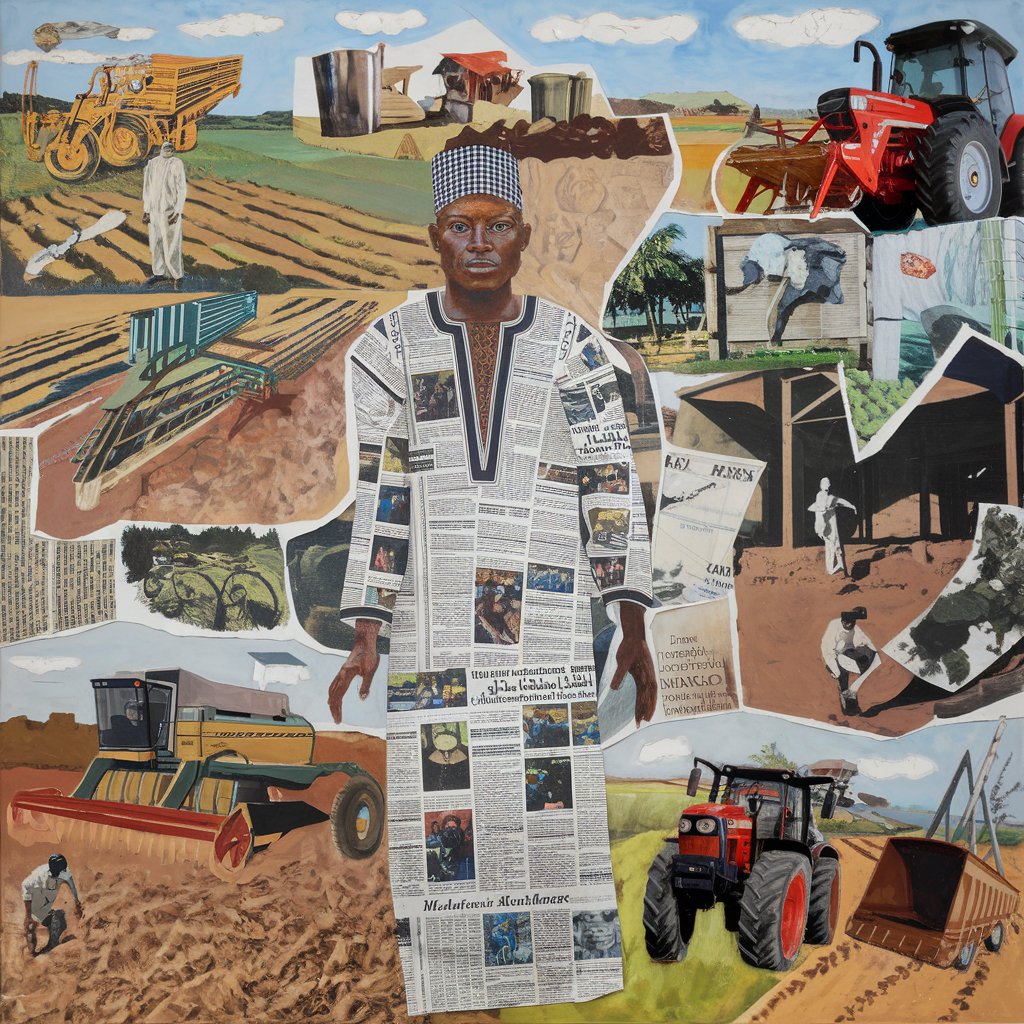

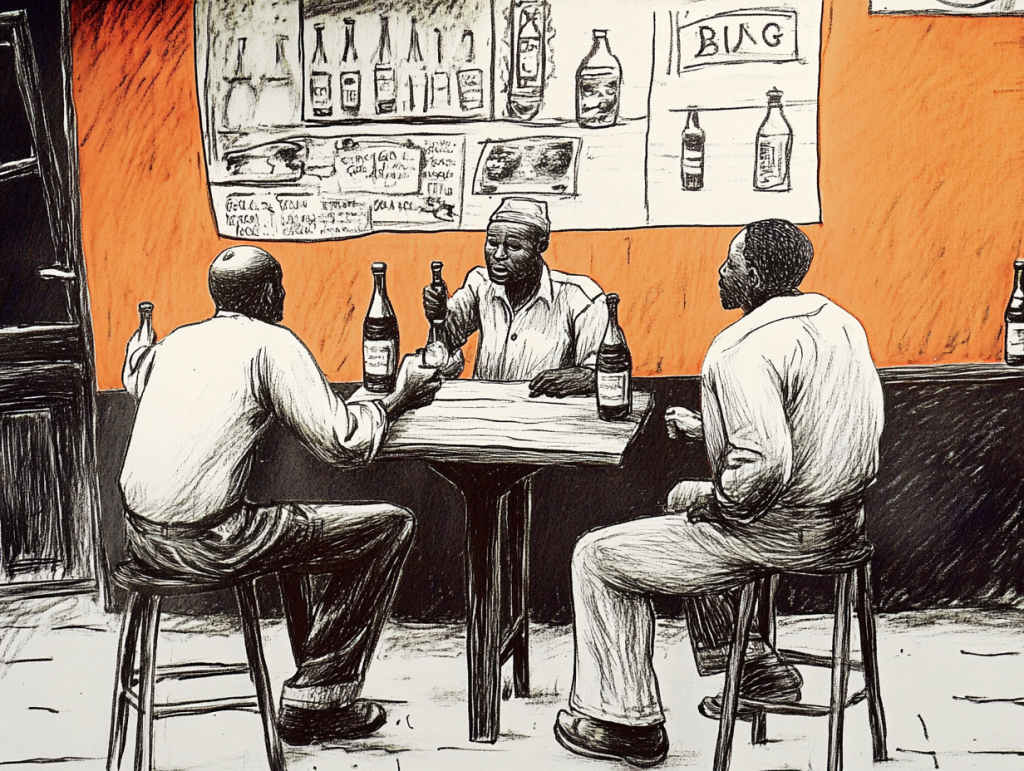

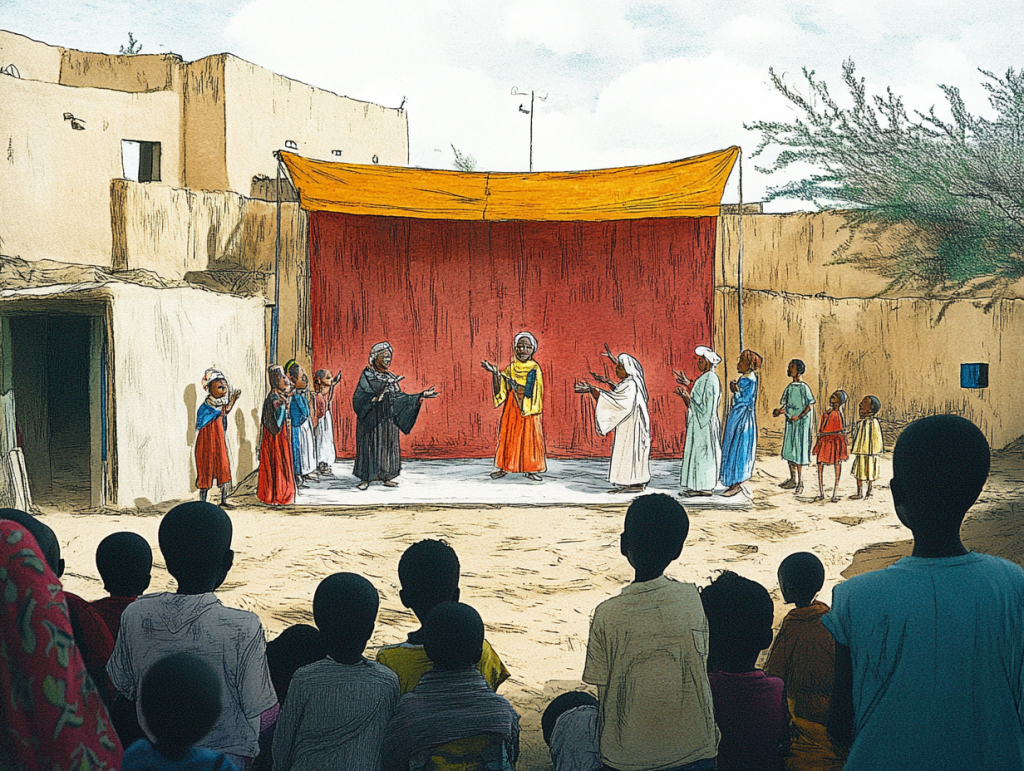

In Chad, the conflict over agricultural land is a problem that affects many regions. Maïbombaye is a canton north of Doba. It is bordered to the north by the canton of Koutou 1, to the south and southwest by the canton of Kara, to the west by the canton of Mongo and to the northwest by the canton of Nassian. The Maibombaye canton is characterized by the severity of its arable land problems, the changes in cultivation practices with the introduction of cash crops, the mechanization of agriculture, and climate change. Access to land has become a source of conflict, giving rise to rivalries between two groups (traditional farmers and modern growers). In this case, the farmers of the Maibombaye canton, represented by the old farmer Ngargoto Ngadog, have created a landscape with ancient over-burned crops everywhere, with various characteristics. There are two farming areas: the first area corresponds to classic gardens, namely: aubergines, taro, melons, etc.); finally, the second crop is limited (rice, corn, and sorghum). In fact, a few years ago in Chad, the increase in the population due to natural growth and emigration, and the transfer of modern agriculture, introduced a profound change in the canton of Maibombaye. In this canton, two groups are arguing over the issue of land and the new methods adaptable in modern agriculture. Traditional farmers use slash-and-burn cultivation methods with materials and tools passed down from generation to generation, such as the hoe, the spade used to turn the soil, the seed drill, a manual instrument for sowing seeds, the jute bag for storing and transporting crops, the plow and draft animals that help to till the soil and transport loads. Their cultivation techniques consist of burning plots of land to prepare the soil and await the arrival of the rain. During a meeting in the courtyard of Ngargoto Ngadog in the Bédogo district, the old peasant, dressed in his traditional raffia outfit, proudly holding his wooden cane, addresses the young villagers with passion and talks about the importance of slash-and-burn cultivation, a practice that has fed generations. He talks about fallow farming, as a system that allowed the land to rest and revitalize, and then urges young people to preserve these ancestral methods with nostalgia: “our ancestors knew what they were doing,” he says. “Don’t be convinced by modern techniques that threaten our land.” The young people, sitting in a circle around him, listen to him attentively but with expressions, visual gestures and murmurs (hum… hum…). Some of these young people had to leave the village to study and have returned with new ideas, inspired by the innovative agricultural methods they discovered. The discussion quickly becomes animated, mixing respect for traditions and the desire for progress.

Nangadoum Mbaingar, a neatly dressed academic representative holding a smartphone displaying agricultural data, respectfully takes the floor, pleading for the modernization of agriculture, arguing that new methods could increase productivity and sustainability. “We must not sweep away our traditions, but combine them with modern approaches,” he says. His tone rises, pointing the finger at the lack of flexibility of the old farmer Ngargoto Ngadog. He adds, “Remaining frozen in the past will not help us face today’s challenges,” he emphasized. Nangadoum Mbaingar (representing academics and modern farmers) adds that our objective is to increase yields, meet the growing demand for food in Chad in general and, in particular, boost food security in the canton of Maibombaye. Modern farmers argue that traditional techniques cannot feed a very large population. During this meeting, modern farmers present case studies where their methods have increased harvests three or four times. In a demonstration, Nangadoum presents cotton and rice fields in Ouagadougou, in the Republic of Burkina Faso, praising the merits of crop rotation and controlled irrigation in Burkinabe soil. Nangadoum Mbaingar is trying harder and harder to convince the farmers that the new methods can coexist with the old ones, but mistrust persists on both sides.

Tension is rising on both sides. Meanwhile, other young traditional farmers are starting to support Nangadoum in what he has to say. They talk about the risks of climate change and the need to use modern technologies to maximize yields. The old farmer Ngargoto Ngadog, although respected, seems frustrated by their resistance to the imposition of foreign culture in this village. The discussions become increasingly heated, with each side defending its position. The group of modern farmers want to evolve, while the other camp insists on the wisdom of the ancestors. This disagreement creates discussions and a feeling of mistrust between the two groups. Ngargoto Ngadog suggested that they are often ignored and disrespected by the younger generation who have returned from their studies and consider themselves to be “experts”. These young people see us as resisting agricultural development in the Maibombaye canton. This lack of mutual understanding contributes to the divide between the two groups. The meeting ended on a note of disagreement. However, in view of this divergence, how can we get these two groups (traditional farmers and modern growers) to speak the same language, unite and protect their natural resource?

Later, a second meeting was held in the court of His Majesty Belém Ngariguem to discuss agricultural practices and the future of the canton of Maibombaye. This meeting brought together young villagers from the said canton, other elders from the villages of Bédog-nang, Bégoud-bé and Nassian, including wise men such as (Ndoha Marie, Mondoumngar Gabriel, Nadjihorbé Pierre, Ngarbarem and Ngarndo Mbatro, aged 69 to 86 respectively); mediation experts, as well as private and public media. During this meeting, discussions often centered on the need for a dialogue between tradition and modernity. In their speeches, the modern farmers continued to express their desire to incorporate modern techniques to improve productivity, while the traditional farmers still insist on the importance of preserving the traditional methods that have proven their worth. Taking the floor, the chief of the canton, His Majesty Belém Ngariguem, called on the elders, the mediation experts, and the private and public media to assist him in this quest for peace, in order to promote the development of his territory. He emphasized the importance of collaboration between the various stakeholders to overcome agricultural and social challenges, while ensuring a prosperous future for his community. In the middle of the crowd that had come to attend the meeting, the midwife Ndoha nodded and snapped her fingers.

When old Ndoha took the floor, she sang an old song from her time, evoking the spirit of solidarity that united the village’s daughters and sons. In this song, she recalls that parents in the past generously offered land to neighbors without expecting anything in return. Ndoha quickly positioned herself as an essential mediator. Aware of the dangers that this conflict represents for the community, she mentioned that the division between traditional farmers and modern growers can seriously affect food security throughout the canton. Mondoumngar Gabriel, Ngarndoh Mbatro, Ngarbarem and Nadjihorbé Pierre insisted on the need to suspend this meeting and subsequently proposed the opening of workshops in the near future. This proposal was accepted and acclaimed by the speakers from different villages and backgrounds.

The following day, in the village of the wise Mondoumngar Gabriel in Bédokassa, practical workshops were organized, bringing together wise men such as Ndoha, Nadjihorbé Pierre, Ngarbarem and Ngarndo, experts in modern agriculture led by Ngarari Ousmane, traditional practitioners led by the young man Allasra Olivier and Mrs. Saratou Marthe, as well as journalists, represented by the private press delegate of Radio Lotiko, Mr. Djimounoum Arnaud, and the public press delegate, Ms. Marie Ngounyom. This workshop addressed several topics, the first of which focused on: “Youth as the spearhead for peaceful coexistence and a key player in the development of food security”. The second focused on “The Evaluation of Traditional and Modern Agricultural Techniques”. For the experts, this workshop is a forum for discussion to address the challenges that are undermining the successful take-off of the Maibombaye canton. These initiatives will enable us to promote a better understanding and encourage mutual collaboration between farmers and modern growers. During this meeting, several modern techniques for improving agriculture were discussed by the young villagers. The atmosphere was charged with anticipation, with everyone hoping to find common ground.

The elders shared their expertise on traditional methods. Ndoha explained that slash-and-burn farming had fed their ancestors. Ngarndo added that fallowing allowed nature to regenerate. Mondoumngar mentioned that social peace is a guarantee of unity and development in a community. Nadjihorbé Pierre and Ngarbarem illustrate the coexistence of traditional farmers and modern growers in these terms: “when the wise and the innovative join forces, the land prospers and the village flourishes”. On the other hand, journalists and experts mention that this collaboration between traditional farmers and modern growers is essential for the future of our agriculture. By combining ancestral wisdom and contemporary innovations, we can create sustainable solutions that respect our heritage while meeting today’s challenges. Ngarari Ousmane and Allasra Olivier explained the benefits of traditional and modern methods for improving agriculture and yields while respecting the environment of their successes, but also the challenges they faced. Such as the use of technologies, namely (tractors for plowing, sowing and transportation; sprayers to apply pesticides and fertilizers evenly; combine harvesters to harvest crops quickly and efficiently; Drip irrigation for precise and water-efficient watering; Agricultural drones to monitor crops and collect data, etc.) Traditional farmers and modern growers were initially skeptical of each other. They began to reposition themselves to follow the training with great interest.

As the exchanges progressed, the initial tensions began to subside. The participants realized that they had common goals: to feed their families and protect their land. The journalists, witnesses to this transformation, took notes ready to share this story of unity.

Finally, the old farmer Ngargoto Ngadog and Nangadoum Mbaingar, very moved, proposed to combine traditional and modern practices. The two groups decided to work on pilot projects, joining forces to develop agriculture in the canton of Maibombaye. His majesty the chief of the canton of Maibombaye and the elders validated this approach for unity and good living together.

FROM CONFLICT TO PEACE

The conflict over agricultural land in Maïbombaye represents a marked polarization between two groups: traditional farmers and modern growers. Entrenched prejudices and mistrust have often led to verbal confrontations, making coexistence difficult. The traditional farmers and the newcomers, instead of seeing themselves as potential partners, consider themselves to be irreconcilable adversaries. However, the intervention of the elders has made it possible to lay a new foundation of peace in this canton. Experts and journalists offer an inspiring example of depolarization. Thanks to their peaceful and inclusive approaches, they have been able to create a space for dialogue. This process shows that, even in situations of intense conflict, it is possible to initiate positive change through dialogue and mutual understanding. At the end of this consultation, the elders and young people of the canton of Maibombaye jointly proposed to create an association called Al-nodji ” “Sepulchre of Harmony, Land of Desolation”, which will now bring together all the daughters and sons of the canton and those from outside in order to further encourage communication, strengthen social justice, encourage community cooperation and support economic development in and around the canton of Maibombaye. This workshop marks a decisive turning point. The elders and the young, once perceived as enemies, now see each other as allies. The media played an important role in the revival of reconciliation between traditional farmers and modern cultivators in this foundation advocated by the wise men and women such as Mondoumngar Gabriel, Ndoha Marie, Nadjihorbé Pierre, Ngarbarem and Ngarndo Mbatro. These journalists broadcast live programs, interviews and feature articles. This reconciliation has inspired other villages to consider similar initiatives.

Ultimately, the conflict over the management of agricultural land in Maïbombaye illustrates the challenges faced by many communities in Chad. However, the example of Ndoha and its continuation demonstrates that with wisdom and will, it is possible to overcome divisions and build peaceful coexistence. By promoting dialogue and collaboration. Communities can not only resolve their differences, but also strengthen their resilience in the face of future challenges. The road to peace is long, but every step towards mutual understanding is a step in the right direction.

In Chad, the conflict over agricultural land is a problem that affects many regions. Maïbombaye is a canton north of Doba. It is bordered to the north by the canton of Koutou 1, to the south and southwest by the canton of Kara, to the west by the canton of Mongo and to the northwest by the canton of Nassian. The Maibombaye canton is characterized by the severity of problems with arable land, changes in cultivation practices with the introduction of cash crops, the mechanization of agriculture, and climate change. Access to land has become a source of conflict, giving rise to rivalries between groups (traditional farmers and modern growers). In this case, the farmers of the Maibombaye canton, represented by Ngargoto Ngadog, have created a landscape with old over-burned crops everywhere, with various characteristics. There are two areas of cultivation: the first area corresponds to classic gardens, namely: aubergines, taro, melon, etc.). Finally, the second crop is destined for limited exploitation (rice, corn, and sorghum).

In fact, a few years ago in Chad, the increase in the population due to natural growth and emigration, and the transfer of modern agriculture, introduced a profound change in the canton of Maibombaye. In Maibombaye, two groups are arguing over the issue of land and the new methods adaptable in modern agriculture. Traditional farmers use slash-and-burn cultivation methods (with tools such as the hoe, the cart, the daba, etc.). This cultivation technique involves burning hectares of plots of land to prepare the soil for the arrival of the great rain. During a meeting in the courtyard of Ngargoto Ngadog, an old farmer, addresses the young villagers with passion. He talks about the importance of slash-and-burn farming, a practice that has fed generations. He talks about fallowing, a system that allowed the land to rest and revitalize itself, and urges young people to preserve these ancestral methods; “our ancestors knew what they were doing,” he says. “Don’t be persuaded by modern techniques that threaten our land.” evokes with nostalgia the agricultural heritage passed down by his ancestors.

The young people, sitting in a circle around him, listen attentively but with expressions, visual gestures (wrinkled, red eyes, overexcited) and murmurs (hum… grum… woo-hoo). Some of them have left the village to pursue their studies, and they return with new ideas, inspired by the innovative agricultural methods they have discovered. The discussion quickly becomes animated, mixing respect for traditions and the desire for progress.

Nangadoum, the youngest representative of the academics, respectfully takes the floor, pleading for the modernization of agriculture, arguing that the new methods could increase productivity and sustainability. He also mentions, “We must not sweep away our traditions, but combine them with modern approaches,” he declares. His tone rises, he points the finger at the old farmer’s lack of flexibility. “Remaining frozen in the past will not help us face today’s challenges,” he emphasized. According to Nangadoum Mbaingar (representative of modern farmers), their objective is to increase yields and meet the growing demand for food in Chad in general and in the canton of Maibombaye in particular. They maintain that traditional techniques cannot feed a growing population. Modern farmers show case studies where their methods have made it possible to increase harvests three or four times over. During a demonstration, a modern farmer presents fields of cotton and rice from Ouagadougou in the Republic of Burkina Faso, extolling the merits of crop rotation and controlled irrigation in Burkinabe soil. Nangadoum Mbaingar tries to convince the farmers that the new methods can coexist with the old ones, but mistrust persists.

Tension mounts on both sides. Meanwhile, other young people begin to support Nangadoum. They talk about the risks of climate change and the need to use modern technologies to maximize yields. Ngargoto, although respected, seems frustrated by their resistance to the idea of preserving proven practices. The discussions become increasingly heated, with each side defending its position. The group of modern, so-called academic farmers want to evolve, while the group of traditional farmers insists on the wisdom of their ancestors. This disagreement creates discussions and a feeling of mistrust between the two groups. According to Ngargoto Ngadog, who represents traditional farmers, they are often ignored and disrespected by the younger generation who have returned from their studies and who say, “I know my rights”. The latter perceive the farmers as resisting agricultural change in the canton of Maibombaye. This lack of mutual understanding contributes to the divide between the two groups. The meeting ends on a note of disagreement. However, in view of this divergence, how can we get the two groups (traditional farmers and modern growers) to speak the same language, unite and protect their natural resource?

Later, a second meeting was held in the canton court of His Majesty Belém Ngariguem to discuss agricultural practices and the future of the canton of Maibombaye once again. This meeting brought together young villagers from the said canton, elders from other villages such as the wise men (Ndoha Marie, Mondoumngar Gabriel, Ngarndo Mbatro and Ngarbarem respectively aged 69 to 83), and even outside experts, private and public media invited to share their knowledge with the young people of the canton of Maibombaye. During this meeting, discussions often centered on the need for a dialogue between tradition and modernity. The young farmers in attendance continued to express their desire to incorporate modern techniques to improve productivity, while the farmers still insist on the importance of preserving traditional methods that have proven their worth. Taking the floor, the chief of the canton instructs the elders and the public and private media to help him in this quest for peace so that his territory may progress. In the middle of the crowd that has come to attend the meeting, the elder Ndoha nods and clicks her fingers to ask for the floor. Taking the floor, she positions herself as an essential mediator. Aware of the dangers that this conflict represents for the community. She knows that the division between traditional farmers and modern growers could lead to food, social and economic insecurity for the whole village. Mondoumngar Gabriel and Ngarndoh insist on the suspension of this meeting and subsequently propose that workshops be opened in the near future. The proposal is accepted and acclaimed by speakers from different villages and backgrounds.

The following day, in the village of Mondoumngar Gabriel in Bédokassa, practical workshops were organized, bringing together wise men such as Ndoha and Ngarndo, experts in modern and traditional agriculture, as well as journalists led by the director of human resources of Lotiko radio in Sarh, Mr. Djimounoum Arnaud. Under the themes: “youth spearheading peaceful coexistence, a player in the development of food security”. “Evaluation of modern techniques”. Practical workshops, debates on sustainability and education and awareness-raising. This workshop is intended as a forum for exchange between young people to experiment with modern techniques while learning the principles of ancestral agricultural practices. These initiatives have fostered better mutual understanding and encouraged mutual collaboration between generations. During this meeting, several modern techniques for improving agriculture were discussed by the young villagers. The atmosphere was charged with anticipation, with everyone hoping to find common ground.

The elders took the floor to share their knowledge of traditional methods. Ndoha explained how slash-and-burn farming had fed their ancestors and maintained the balance of the land. Ngarndo added that fallowing allowed nature to regenerate. The young farmers, who had been skeptical at first, began to listen carefully.

Then the experts presented modern methods, such as precision agriculture and water resource management. They showed how these methods could improve yields while respecting the environment, as well as the successes and challenges they faced. Such as the use of technologies like sensors and drones to monitor crops and optimize the use of water and fertilizers, the soilless cultivation method, where plants are fed with nutrient solutions, saving water and increasing yields, and the combination of traditional and modern agricultural practices, with an emphasis on crop rotation.

As the discussions progressed, the initial tensions began to subside. The participants realized that they had common goals: to feed their families and protect their land. The journalists, witnessing this transformation, took notes ready to share this story of unity.

Finally, an emotional Ngargoto Ngadog, the elder, suggested combining traditional and modern practices. Together, the two groups decided to work on pilot projects, joining forces to develop agriculture in the canton of Maibombaye. His majesty, the chief of the canton of Maibombaye, and the elders, validated this approach to unity and living together.

FROM CONFLICT TO PEACE

This workshop marks a turning point. The old and the young, once perceived as enemies, now see each other as allies. The media played an important role in the revival of reconciliation between traditional farmers and modern growers in this foundation advocated by the wise men Mondoumngar, Ndoha and Ngarndo. These journalists attended the workshop and broadcast live reports, interviews, feature articles and radio and television programs showing the exchanges between elders and experts. This reconciliation has inspired other villages to consider similar initiatives.

The conflict over agricultural land in Maïbombaye represents a marked polarization between two groups: traditional farmers and modern cultivators. Entrenched prejudices and mistrust have often led to verbal confrontations, making coexistence difficult. The traditional farmers and the newcomers, instead of seeing themselves as potential partners, have often considered themselves to be irreconcilable adversaries. However, the intervention of wise men such as Ndoha, Mondoumngar and Ngarndo, followed by experts and journalists, offers an inspiring example of depolarization. Thanks to their peaceful and inclusive approaches, they have been able to create a space for dialogue. This process shows that, even in situations of intense conflict, it is possible to initiate positive change through dialogue and mutual understanding. At the end of this consultation, the elders proposed, in agreement with the young people of the canton, to create a good neighbor association, LO-NODJI, which brings together all the daughters and sons of the canton, even those from outside, without distinction. This initiative will further strengthen living together and promote peace in the community. Thus, the conflict, which could have led to a deeper division, becomes a catalyst for unity and solidarity within Maïbombaye, thanks to the commitment and wisdom of eminent elders such as Mondoumngar Gabriel, Ndoha Marie and Ngarndo Mbatro.

The conflict over the management of agricultural land in Maïbombaye illustrates the challenges faced by many communities in Chad. However, the example of Ndoha and his followers shows that with wisdom and willpower, it is possible to overcome divisions and build peaceful coexistence. By promoting dialogue and collaboration, communities can not only resolve their differences, but also strengthen their resilience in the face of future challenges. The road to peace is long, but every step towards mutual understanding is a step in the right direction.

Note: This text is the result of a workshop and may be someone’s first written long lenght article, it may therefore contain imperfections.