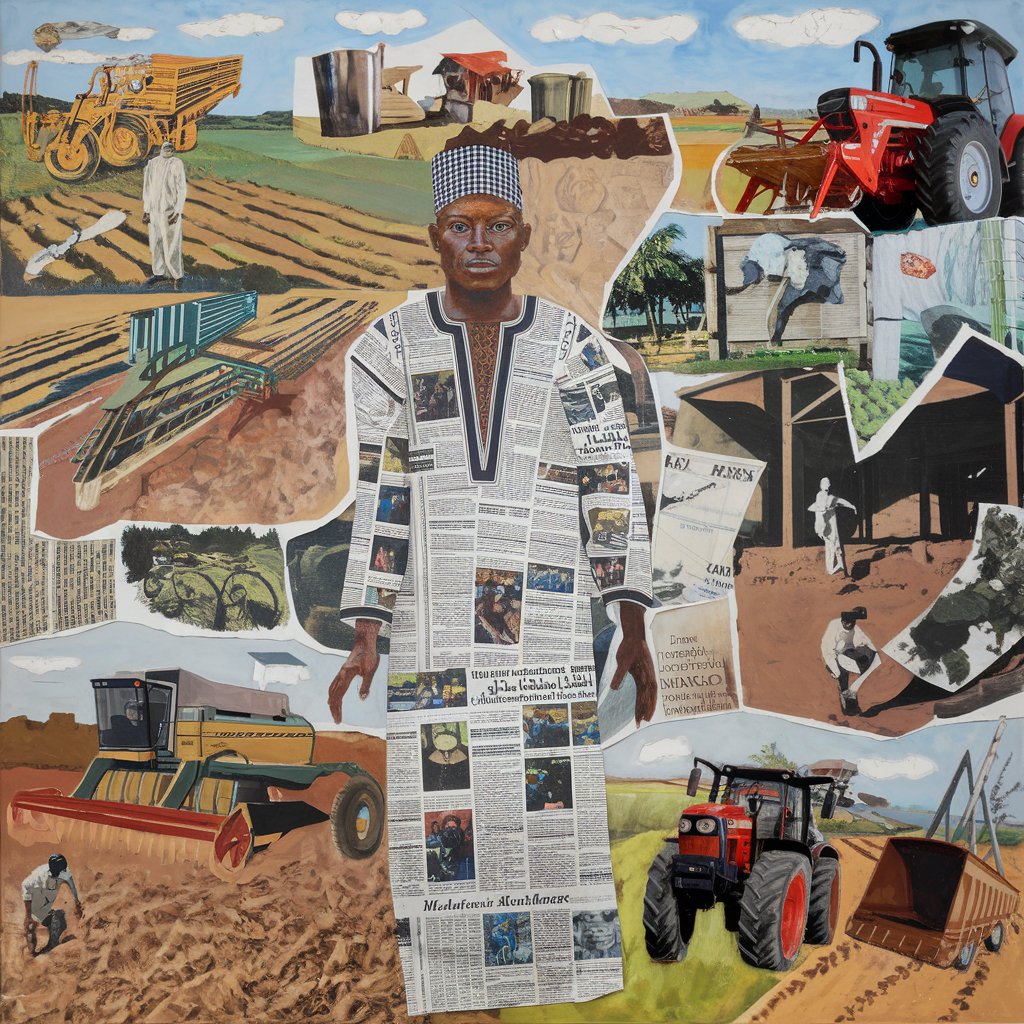

Chad, with its diversity of religions, cultures and traditions, makes inter-religious marriages a sensitive and often controversial subject. In N’Djamena and other cities, religious and ethnic differences often complicate the union of two individuals, fuelling prejudice and social challenges. However, for some, love transcends these barriers. The story of Nembaye and Abakar illustrates how determination and love can overcome prejudice.

Between confrontation and parental opposition

The weight of tradition and religious beliefs has a profound influence on marriage in Chad. In N’Djamena, a capital city where different religions, traditions and cultures mix, Nembaye and Abakar met and developed a loving relationship. Nembaye, a Christian, and Abakar, a Muslim, saw their relationship negatively judged by their families, who saw it as an adventure doomed to failure. When the couple announced their intention to marry, they faced strong parental opposition, as the beliefs and traditions of each family seemed insurmountable. Yet despite these obstacles, they continued to fight for their love, convinced that their union could transcend religious and cultural barriers. Their story reflects the challenges faced by interfaith couples in Chad, in a society where tradition and religion play a crucial role in marital choices.

Parents, often influenced by deep-seated prejudices, perceive these marriages as a threat to the preservation of family and community values. Parental opposition, often motivated by fear of social rejection, manifests itself in categorical refusal of the union. In the Nembaye community, the idea of marrying a Muslim evokes painful memories of past insults and discrimination. ‘ One evening, the sun was just setting over Ndjamena, bathing the city in a golden light ’, begins Nembaye, with a pensive look. ‘ I was sitting in the family courtyard, trying to figure out how to tell my father about my relationship with Abakar and our intention to get married. I was afraid of his reaction, but I knew I had to face this conversation.” She continues, ‘That evening, I summoned up all my courage. I approached him, who was sitting down, concentrating on a newspaper. My heart was pounding, but I finally said: Dad, I have something important to tell you. Abakar and I… we’re in love and we want to get married. He put down the newspaper, his gaze turning cold and hard. In anger, he stood up abruptly and shouted: – With a doum (the term used by some southern communities to refer to Muslims from the north)? Do you want to marry a Muslim? Do you want to destroy your life, Nembaye? Do you want our family to become the shame of the neighbourhood? The same Muslims who used to call us abide (Arabic for slave), hafine (who smells or is an infidel) and kirdi (a derogatory term used to describe southerners as miscreants), do you want to marry them? Do you want your children to be called farack (bastard)? His face was red with anger, and his words echoed through the courtyard like a thunderclap. I froze, my courage gone in the face of his violent reaction. There was nothing but contempt and fear in his words, ethnic and religious prejudices so ingrained that they blinded his judgement. I realised how difficult it would be to make our love accepted, and that the road to our happiness would be strewn with obstacles’, says Nembaye, full of emotion. Her father’s cry from the heart and his opposi

tion to the union reveal the ethnic and religious prejudices that can influence family decisions, preventing Nembaye’s feelings for Abakar from blossoming. For her father, there is no question of his daughter ending up in such a marriage, risking the loss of her traditional and religious values. He is worried that his future grandchildren will be treated as ‘farack’, that is, bastard children or children who are not recognised. His attempts to explain to his father that Abakar was different were quickly silenced. This type of parental rejection is often based on historical or cultural experiences that drive a wedge between families of different faiths. The parents’ reluctance to accept an inter-religious marriage reflects their fear of seeing their child depart from their own tradition.

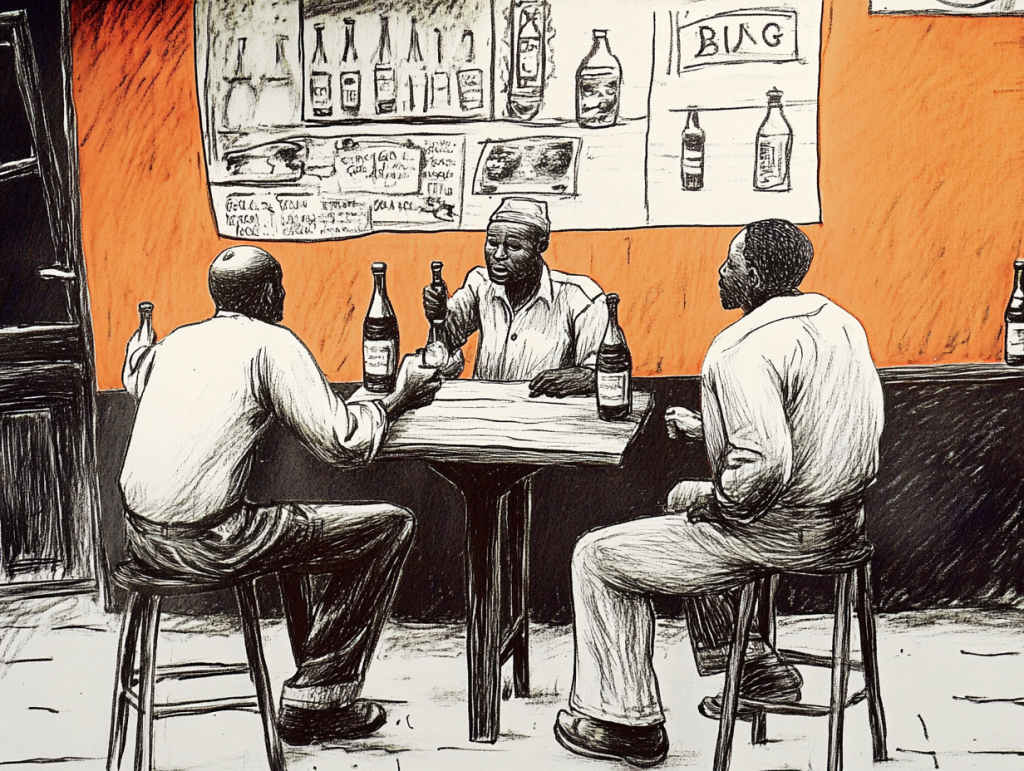

Abakar, on the other hand, faces the same resistance. ‘My father, faithful to his traditions, reminds me that love is not always enough to overcome differences, when I tell him of my intention to marry Nembaye,’ he confides. There are many reasons for

this opposition. On the one hand, the parents fear that their children will not be able to preserve their family traditions and religious practices in an inter-religious marriage. ‘My father fears that Nembaye will never understand the depth of the Muslim faith and will not be able to bring up our children in that faith,’ continues Abakar. ‘She won’t be able to raise our children in the Muslim faith. This marriage is a mistake,’ says my father gravely , ’Abakar tells us. There is also social pressure. Families fear the judgement of the community. Unions between people of different religions are often seen as a betrayal, both religious and cultural. The parents of Nembaye and Abakar do not want their children to be marginalised or to be viewed unfavourably by society. These external considerations, linked to honour and social status, come on top of spiritual concerns. This opposition reveals the gulf between these two worlds, where each parent fears that the other religion will compromise their family’s faith and values.

Resilience and determination

Despite fierce opposition from their parents, Nembaye and Abakar refused to let their families decide their future. Their love, born against a backdrop of deep religious and cultural divisions, drove them to defy all expectations. ‘Nembaye and I continued to see each other in secret,’ says Abakar with a smile. ‘Each meeting was both a stolen moment and a source of anguish. Sometimes, Nembaye would cover herself with a scarf so as not to be recognised and would slip out of her house at nightfall to come and meet me. I’d wait for her, my eyes worried, glancing around nervously. Every kiss, every gentle word was tinged with palpable anxiety. But their love gave them the strength to carry on, to believe that they could overcome all the obstacles. ‘Things got complicated when Nembaye told me she was pregnant,’ admits Abakar gravely. ‘When I told my father about my pregnancy, his reaction was immediate and brutal,’ says Nembaye. ‘Get out of this house immediately! You’re not my daughter any more,’ screamed my father, unable to hold in his anger . Driven out by her father, Nembaye hoped to find refuge with Abakar. However, Abakar’s family is not ready to take her in either. ‘ When I arrived at Abakar’s house, to my great surprise, his mother told me: ‘You don’t belong here’, Abakar’s mother said coldly,’ says Nembaye. Thereafter, she found herself without support, rejected by both families.

Despite the pain and uncertainty, Abakar refused to abandon Nembaye. Together, they decide to flee, far from their families who disapprove of their union. Every day is a challenge, marked by fear of the future and constant doubts, but their love remains their strength, uniting them against all odds. The days go by, difficult and uncertain, but Nembaye and Abakar hold firm. Their families keep up the pressure, hoping to see them give up this relationship they consider impossible. But nothing seems to be able to break their determination. Year after year, they persist, refusing to give in to the social and religious norms that keep them apart. In the end, their patience and love won out. ‘ After years of resistance, our families finally accepted our union,’ says Abakar, his voice filled with emotion. Their struggle was not in vain.

Today, Nembaye and Abakar lead a peaceful life in Bongor. Their three children, born of this solid love, represent the victory of their resilience. They represent a bridge between two cultures and religions that were once in conflict, but are now united in harmony.

Perceptions of Nembaye and Abakar’s entourage

The marriage between Nembaye and Aabakar has left no one indifferent. Their supporters also had something to say about the marriage and their views on it. The couple’s inter-religious marriage, which is generally regarded as forbidden by Chadian society, has given rise to, and continues to give rise to, divided opinions among those around them. Neighbours, friends and even some members of the extended family viewed the union between Nembaye and Abakar with initial suspicion, often influenced by religious prejudice. However, over time, as Nembaye and Abakar managed to prove that their love was solid and they managed to maintain a balance between their two religions, despite the prejudices of their parents and those around them, perceptions changed: ‘ At first, everyone looked at us as if we were rebels or a curse,’ recalls Abakar. ‘ But now our neighbours and friends see that our marriage is based on respect. They see us as an example of tolerance. Some young people say they want to follow our example, but they are still held back by fear.’

The people around them, who were initially critical of this union, have come to recognise the strength of their love and the solidity of their family. ‘ I had my doubts at the beginning of their relationship ’, confides a neighbour, “ but they have shown that love can overcome even the most rigid traditions ”.

This couple’s story shows that love and perseverance can overcome even the most entrenched prejudices. ‘After years of struggle, we finally accepted their union, realising that their love is stronger than religious differences. In the end, Abakar brought us Nembaye’s dowry, something I wanted so much at first,’ says Nembaye’s mother with a touch of humour. They settled in Bongor and brought up their three children with respect for both religions: the two boys followed their father’s Muslim faith, while the youngest daughter accompanied her mother to the Catholic church. This coexistence of two religions in the same family is an example of tolerance and mutual respect.

‘ Abakar and Nembaye have been given this challenge because they are open-minded,’ says one of the cousins I met in Bongor. I don’t know if it’s due to his studies elsewhere, but he has a good sense of communication and respect for everyone. It’s all these qualities that have perhaps made this risky marriage a success,’ adds his cousin. They have found a balance that allows their children to grow up in an environment of tolerance. Their lives and their religious differences have been a source of cultural enrichment, not an obstacle to their love.

Inter-religious marriages, although difficult, can sometimes be an opportunity to bring together two communities or two groups that in the past were divided. The story of Nembaye and Abakar is a vivid illustration that despite preconceived ideas and parental opposition, love and willpower can win the day. But to achieve this, ‘ tolerance, respect for differences, respect for each other’s culture and mutual understanding are needed to break down barriers and build a bridge between our cultures and religions’, says Pastor Madjitoloum Olivier with serenity. This example of the cohabitation of different faiths could inspire the whole of Chadian society, which is in the throes of change, where traditions remain strong and where acceptance of differences is becoming increasingly crucial to building a common future.